The ‘Long COVID-19 Syndrome’

Sandor Szabo, MD, PhD, MPH

Founding Dean and Professor, School of Medicine

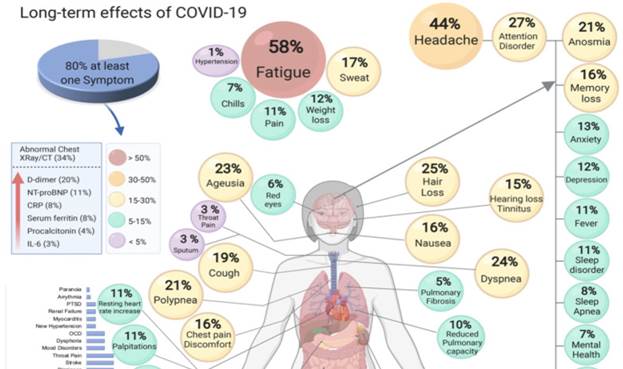

COVID-19 started as an acute respiratory disease due to inhalation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and indeed most of the illnesses were of short duration (1). But as the pandemic spread around the world, complicated cases started to appear, i.e., some patients had long-standing respiratory problems, associated with fatigue, muscle weakness, and other signs or symptoms that are not typical of acute respiratory diseases which usually end quickly, and then patients recover. Clinicians were alarmed when they started to see returning patients who had completely recovered after acute COVID-19, but 4-8 weeks later came back, not only with breathing problems but severe, almost paralyzing fatigue, neurologic problems, headache, impaired memory labeled “brain fog,” as well as other organ dysfunctions, especially in the endocrine and gastrointestinal systems:

The long-term effects of COVID-19. (Adapted from S. Lopez-Leon et al. More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv 2021 Jan 30;2021.01.27.21250617)

When these long-duration cases started to appear in the scientific literature, they were labeled as ‘long-haulers,’ ’chronic COVID-19,’ ‘complicated COVID,’ etc., but the now prevailing designation seems to be ‘long COVD-19’ disease. However, this is not a simple ‘disease’ referring to the involvement of a single organ with a single lesion (e.g., infection or tumor). Rather, as discussed and illustrated above, this is a complex syndrome involving multiple organs with several lesions, constantly changing new or waning signs and symptoms. For these reasons, we prefer and propose to call it ‘long COVID-19 syndrome’ (LCS), which is defined by at least two or three objective signs and subjective symptoms remaining (not disappearing) that are continuing four weeks after the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and acute COVID-19 disease. But since we now know that LCS may develop even in people who have had only a mild disease or had been asymptomatic after a proven infection by the virus, it is an important part of the definition that SARS-CoV-2 infection must be documented by PCR or antibody laboratory tests. Otherwise, as a large recent French study demonstrated (2), the label of LCS may lead to confusion and an unnecessary diagnosis of LCS – similar to the poorly understood and never objectively defined ‘chronic fatigue’ syndrome.

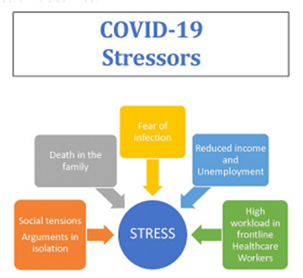

Because of the multifaceted presentation of LCS, based on multifactorial mechanisms, it is not surprising that a ‘post-COVID-19 stress syndrome’ has also been recognized (1, 3). Namely, since stress is defined by Hans Selye (4) as the ‘nonspecific response of the body to any demand upon it’ that, also by definition, must be caused by multiple factors (different in nature, e.g., biologic, chemical, psychosocial causative agents), COVID-19 is the greatest new human stressor. These stressors include not only the causative virus, but the severity of the disease, and the personal, psychosocial suffering (often associated with the frustration of isolation, loss of income, and death in the family, among others) (3). The ‘post-COVID-19 stress syndrome’ can also be part of LCS and it is well defined by typical endocrine (e.g., initially elevated, then decreased secretion of cortisol, related to the exhaustion of the adrenal glands), and other metabolic changes.

(Adapted from S. Szabo and P. Zourna-Hargaden: COVID-19: New disease and the largest new human stressor. Integr. Physiol., 2020, 1, 258-265.)

The frequency of LCS is variable in different populations, e.g., the initial prevalence in the U.S. was between 3-30%, but the most recent data from the U.K. indicate that 2.5% of the entire population experience various forms of LCS! Furthermore, the initial Israeli data showed that based on the self-reported vaccination status, fully vaccinated participants who had also had COVID-19 were 54% less likely to report headaches, 64% less likely to report fatigue, and 68% less likely to report muscle pain than were their unvaccinated counterparts (5). But the U.K. data revealed that, although prior vaccination offers some protection against LCS, LCS may still occur even in 25% of fully vaccinated people (6).

As for any complex disease, there is no way to predict who may develop LCS. This pessimistic prediction also stands for the prevention and treatment of LCS. But as we know from many multifactorial diseases, multivitamins, especially those with antioxidant potentials such as large doses of vitamins C and E as well as minerals such as selenium and zinc may also be beneficial. Furthermore, since many of the long-term complications of COVID-19 include vascular thrombo-embolic multiorgan lesions, small doses (e.g., 81 mg) of aspirin will likely be beneficial, as has just been demonstrated in hospitalized COVID-19 patients (7).

Thus, although “long COVID largely remains a mystery,” new clues are emerging (8) not only to its pathogenesis, i.e., mechanisms of development but also to its prevention and treatment. Nevertheless, more basic research is needed, as well as clinical and public health investigations, to fully elucidate the mechanisms and understand the manifestations of LCS.

Watch Dr. Sandor Szabo explains the Long COVID syndrome:

References

- Szabo S. COVID-19: New disease and chaos with panic, associated with stress. Med. Sci., 2020;59:41-62.

- Slomski A. Belief in having had COVID-19 Linked with long COVID symptoms. JAMA,2022;327(1):26. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.23318.

- Szabo S., Zourna-Hargaden P. COVID-19: New disease and the largest new human stressor. Integr. Physiol., 2020;1(4):258-265.

- Szabo, S., Tache, Y., Somogyi, A. The legacy of Hans Selye and the origins of stress research: A retrospective 75 years after his landmark “letter” in Nature. Stress, 2012;15(5):472–478.

- Kreier F. Long-COVID symptoms less likely in vaccinated people, Israeli data say. Nature, January 25, 2022.

- Marshall M. Beating Long COVID: Long-haul fight. New Scientist, Feb.26, 2022.

- Chow J.H. et al. Association of early aspirin use with in-hospital mortality in patients with moderate COVID-19. JAMA Network Open, 2022;5(3):e223890. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.3890.

- Weintraub K. Long COVID largely remains a mystery, but a few clues are emerging. USA Today, Jan. 28-30, 2022.