By: Dr. Neelima Chauhan, Professor – Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences

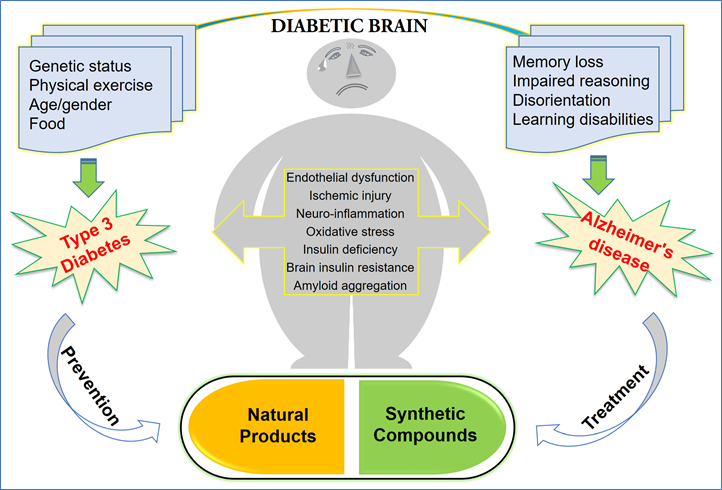

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-dependent neurodegenerative disorder currently afflicting ~6 million Americans. The vast majority (~95%) of diagnosed AD cases are of sporadic origin while only a few percentage (~5%) of diagnosed AD cases account for familial/genetic origin, indicating the importance and role played by non-genetic risk factors during the process of aging that may potentially contribute to the development of AD. Studies show the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease among people with diabetes is 65% higher than that of those without diabetes. With such a strong link, research has focused on explaining the connection between the two diseases.

Type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease share several common abnormalities including impaired glucose metabolism, increased oxidative stress, insulin resistance and amyloidosis, contributing to overlapping pathology. The enhanced risk of developing AD in diabetic patients remains strong even when vascular factors are controlled. While insulin is neurotrophic at optimum concentration, too much insulin in the brain may be associated with reduced amyloid plaque clearance since both insulin and amyloid compete for the availability of the enzyme that degrades them.

In studies of people’s brains after death, researchers have noted that the brains of those who had Alzheimer’s disease but did not have type 1 or type 2 diabetes showed many of the same abnormalities as the brains of those with diabetes, including low levels of insulin in the brain. It was this finding that led to the theory that Alzheimer’s is a brain-specific type of diabetes—”type 3 diabetes.”

In diabetes, if a person’s blood sugars become too high or too low, the body sends obvious signs of the problem: behavior changes, confusion, seizures, etc. In Alzheimer’s disease, however, rather than those acute signals, the brain’s function, and structure decline gradually over time.

When a group of researchers reviewed the collections of studies available on Alzheimer’s disease and brain function, they noted that a common finding in Alzheimer’s disease was the deterioration of the brain’s ability to use and metabolize glucose. They compared that decline with cognitive ability and noted that the decline in glucose processing coincided with, or even preceded, the cognitive declines of memory impairment, word-finding difficulty, behavioral changes and more. Furthermore, scientists determined that as insulin functioning in the brain worsens, not only does cognitive ability decline, but the size and structure of the brain also deteriorate—all of which normally occur as Alzheimer’s disease progresses.