By Sandor Szabo, MD, PhD, MPH, Dean and Professor, AUHS School of Medicine AUHS

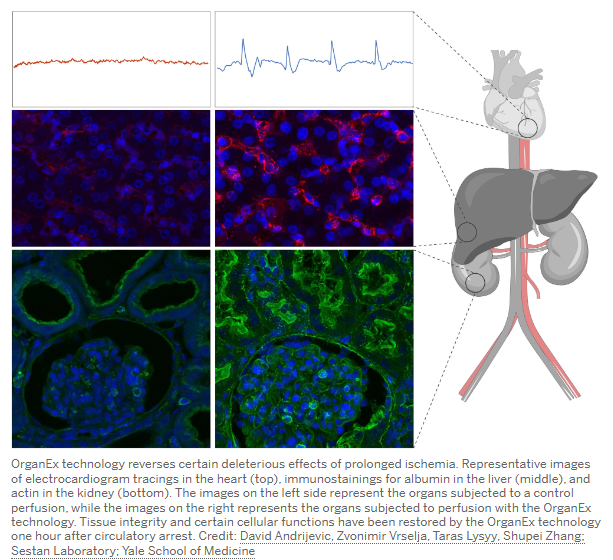

An editorial in the one of the best and most prestigious scientific journals of the world, Nature (Aug. 11, 2022) proclaimed: “Pig organs partially revived in dead animals – researchers are stunned” (1). But the editorial also warns scientists that “the findings aren’t yet clinically relevant, but say the research raises ethical questions about the definition of death.” Namely, in the study, originally published in the Aug. 3, 2022, issue of Nature showed that “pigs that received a blood substitute from a system called OrganEx showed activity in their heart, liver and kidneys after death” (1, 2). The OrganEx was a special solution that contained the animals’ blood and 13 compounds, including anticoagulants and nutrients. This slowed the decomposition and quickly restored some organ function, such as heart contraction and activity in the liver and kidney:

This publication follows the experiments in 2019 by the same scientists at Yale University in which they revived the disembodied brains of pigs four hours after the animals died, calling into question the idea that brain death is final (3).

These studies indeed have major implications for not only the definition of death, but for our teaching students about cell and tissue injury. Namely, we tell medical, pharmacy and nursing students about reversible and irreversible stages of cell injury: in reversible damage (caused by lack of oxygen & nutrients delivery by blood, i.e., ischemia, chemicals, bacteria, or viruses) the injury to the cell membrane or mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum may be reversible if the exposure to the etiologic agent does not last for a long time (4-6). During irreversible cell damage, on the other hand, that involves injury to cell nucleus, there is no return. On the basis of these concepts, reinforced in old and new textbooks of pathology and pathophysiology, we teach students about the sensitivity of our organs to lack of oxygen/blood flow during ischemia (e.g., caused by heart attack). Namely, we teach that our neurons in the brain are the least tolerant to lack of blood flow, followed by myocardium (heart) and tubular epithelial cells (in kidney):

- Irreversible brain damage occurs in 3-5 mins

- Heart myocardium in 15-20 mins

- Renal tabular epithelial damage in 30-40 mins.

These data have important implications in cardio-pulmonary resuscitations (e.g., after heart attack): this is the reason that we need to start resuscitation efforts (i.e., compressing the chest/heart and blowing air through the mouth to deliver at least minimum oxygen to the lungs) as soon as possible, i.e., within 2-3 mins after someone collapses during myocardial infarction. The other practical implication is that harvesting organs (e.g., kidney, liver) should occur as soon as possible after brain death or catastrophic traumatic body injury. The organ harvesting period may be prolonged, if the recently published new finding with harvested pig organs is confirmed by other scientists.

Thus, based on the recently published new results on pig organ preservation after death, we may need to revise what we teach about cell and tissue/organ injury. However, we should not change our practice in providing cardiopulmonary resuscitation after heart attack — at least not for the time being!

References

- Kozlov M. Pig organs partially revived in dead animals – researchers are stunned. Nature, 2022, 608, 247-248.

- Andrijevic D. Vrselja Z. Lyssy T. et al. Cellular recovery after prolonged warm ischaemia of the whole body. Nature, 2022, 608, 405-412.

- Vrselja et al. Restoration of brain circulation and cellular functions hours post-mortem. Nature, 2019, 568, 336–343.

- Szabo S, Nagy L, Plebani M. Glutathione, protein sulfhydryls and cysteine proteases in gastric mucosal injury and protection. Clinica Chimica Acta, 1992, 206, 95-105.

- Szabo S, Kovacs K. Causes and mechanisms of cell and tissue injury in endocrine glands. In: Kovacs K, Asa SL (eds.), Functional Endocrine Pathology (2nd ed.). Boston: Blackwell Science Inc, 1998; 996-1016.

- Szabo S, Tache Y, Tarnawski A. The ‘gastric cytoprotection’ concept of Andre Robert and the origins of a new series of international symposia. In: Filaretova LP, Takeuchi K (eds.): Cell/Tissue Injury and Cytoprotection/Organoprotection in the Gastrointestinal Tract: Mechanisms, Prevention and Treatment. Frontiers of Gastrointestinal Research. Basel, Karger, 2012, 30, 1–23.